- Home

- Lidia Yuknavitch

The Book of Joan

The Book of Joan Read online

Dedication

This book is for Brigid.

Epigraph

“We are all creatures of the stars.”

―Doris Lessing

“Heterosexuality is dangerous. It tempts you to aim at a perfect duality of desire. It kills the other story options.”

―Marguerite Duras

“Be careful what stories you tell yourselves about beauty, about otherness. Be careful what stories ‘count.’ They will have consequences that shiver the planet.”

―The Book of Joan

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Book One Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Book Two Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Book Three Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Advance Praise for The Book of Joan

Also by Lidia Yuknavitch

Text Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Book One

Prologue

In the hundreds of thousands of years before the Chicxulub asteroid impact that led to the mass extinction of dinosaurs on earth, volcanoes in a region of India known as the Deccan Traps erupted repeatedly. They spewed sulfur and carbon dioxide, poisoning the atmosphere and destabilizing ecosystems.

The dinosaurs and most manner of living things were already at death’s door by the time the asteroid hit.

The Deccan Traps changed the ecosystem radically. Blotted out the sun. Death became history, geography rewrote itself. And yet earth was reborn. It was not a miracle that life was destroyed and then re-emerged. It was the raging stubbornness of living organisms that simply would not give in.

Life re-emerged as it always does. From the depths of oceans and riverbeds to the frozen biospheres hidden under ice sheaths to the very core of the world’s underground caves, from the tomb-like otherworlds of earth, matched in diversity and design only by one thing: interstellar space.

The next time a geocataclysm like this happened, the origin was anything but random.

Chapter One

Burning is an art.

I remove my shirt and step toward a table where I have spread out the tools I will need. I swab my entire chest and shoulders with synthetic alcohol. My body is white against the black of space where we hover within a suborbital complex. CIEL.

Through the wall-size window, I can see a distant nebula; its gases and hypnotic hues make me hold my breath. What a puny word that is, beautiful. Oh, how we need a new language to go with our new bodies.

I can also see the dying ball of dirt. Earth, circa 2049, our former home. It looks smudged and sepia.

A fern perched in the window catches my eye. Well, what used to be a fern. I never had a green thumb, even those long years ago when I lived on Earth. This fern is mostly a sad little curve of stick flanked by a few dung-green wisps; it wilts and droops like a defunct old feathery cock. Its photosynthesis is entirely artificial. If it were allowed the “sun” we’ve got now, with the absence of adequate ozone layers, it would instantly die. Solar flares irradiate us daily, even as we are protected by STEs—“superior technological environments,” they’re called.

I’ve not seen CIEL from the outside for a long time, but I remember it looking like too many fingers on a ghost-white hand. Sky junk. Rats in a maze, we are. Far enough from the sun to exist in an inhabitable zone, and yet so close, one wrong move and we’re incinerated. In our man-made, free-floating station, with our rage-mouthed Empire Leader, Jean de Men, fastened at the helm of things. We’re the aftermath of earth-life. CIEL was built from redesigned remnants from old space stations and science extensions of former astro and military industrial complexes. We who live here number in the thousands, from what used to be hundreds of countries. Every single one of us was a member of a former ruling class. Earth’s the dying clod beneath us. We siphon and drain resources through invisible technological umbilical cords. Skylines. That almost sounds lyrical.

The fern, like all green matter at this point, is cloned. And me? As we’ve been told a million times, “radical changes in the ozone, atmosphere, and magnetic fields caused radical changes in morphology.” How’s that for a cosmic joke of the ruling class? The meek really did inherit the Earth. And the wealthy suck at it like a tit. There’s no telling how many meek are left. If any. I sigh so loud I can almost see it leaving my mouth. The air here is thick and palpable.

There is a song lodged in my skull, one whose origin I can’t recall. The tune is both omnipresent and simultaneously unreachable; the specifics drift away like space junk. There are times I think it will drive me mad, and then I remember that madness is the least of my concerns.

Today is my birthday, and pieces of the song from nowhere haunt my body, a sporadic orchestral thundering that rises briefly and then recedes. Sound fills my ears and whole head, a vibration that rings every bone in my body and then nothing. By “birthday,” what I mean is that today marks my last year until ascension. Now, at forty-nine, I’m aging out, a threat to resources in a finite, closed system. CIEL authorities may permit a staged theatrical spectacle when your time is up, but dead is dead, no matter when you lived. At one time, in the early years here, I remember, we still believed that ascension involved some rise into a higher state of being. Not just an escape from a murdered planet to a floating space world, but a climb toward an actual evolution of the mind and soul. It still strikes me as absurd that all our mighty philosophies and theologies and scientific advances were based on looking up. Every animal ever born—blind or stupid or sentient—looked up. What of it? What if it was only a dumb reflex?

I’ve since come to understand that there are simply too many of us for Jean de Men’s Empire to sustain unless we continue to discover new treasure troves left on Earth or evolve into beings who don’t need plain old food and water. Our recycled meat sacks provide water when we die. It’s the one biotechnological achievement we’ve been able to successfully “create” up here. You can get pure water from a corpse. So far in the evolution of the process, they can extract about a hundred liters of water from a fresh corpse—about twenty days’ survival ration. That’s not very efficient.

No one knows if or how fast those odds will improve. We only know we tried space suits and recycled urine and exhalation modes and a whole wave of deaths resulted from the biotoxins. So we continue to draw from mother Earth, to suck her diseased body dry.

The fern and I stare each other down. When I first came here, I was fourteen and dying from unrequited love. Or hormonally unstoppable love at least. I am now forty-nine, in my penultimate year. If hormones have any meaning left for any of us, it is latent at best, lying in wait for another epoch. Maybe we will

evolve into asexual systems. It feels that way from here. Or maybe that’s just wishful thinking. Desperately wishful. My throat constricts. There are no births here. There is a batch of youth in their late teens and early twenties. After that, who knows.

This is my room: stylishly decorated in blue-gray slate slabs. A memory foam bed on a metal slab, a slab of a desk, various metal chairs, a cylindrical one-room shower and human waste purge station. The most apparent thing in my quarters is a one-wall window into space, or oblivion, with a protective shade to help us forget that the sun might eat us alive at any moment, or that a black hole might sneak up on us like a kid playing hide-and-seek.

This is my home: CIEL. A home, forever away from home.

I live alone in my quarters. Oh, there are others here on CIEL. I used to have a husband. Just a word now, like home, earth, country, self. Maybe everything we’ve ever experienced was just words.

“Record,” I whisper to the air in the room around me. This is like what prayer used to be.

“Audiovisualsensory?” A voice that sounds vaguely like my mother’s. Mother: another word and idea fading from memory.

“Yes,” I answer. The entire room vibrates, comes to life, activates to record every move and sound I make.

I mean to give myself two birthday presents before I’m forced to leave this existence and turn to dust and energy. The first is a recorded history. Oh, I know, there’s a good chance this won’t attract the epic attention I am shooting for. On the other hand, smaller spectacles have moved epochs. And anyway, I’ve got that gnawing human compulsion to tell what happened.

The second present is a more physical lesson. I am an expert at skin grafting, the new form of storytelling. I intend to leave the wealth of my knowledge and skill behind. And the last of my grafts I intend to be a masterwork.

I finish applying astringents. My flesh pinkens and screams its tiny objection. I position the full-length mirror in front of me—tilt it to bear the weight of my entire body’s reflection. The song plays and plays in my head and rings in my rib cage now and again.

I am without gender, mostly. My head is white and waxen. No eyebrows or eyelashes or full lips or anything but jutting bones at the cheeks and shoulders and collarbones and data points, the parts on our bodies where we can interact with technology. I have a slight rise where each breast began, and a kind of mound where my pubic bone should be, but that’s it. Nothing else of woman is left. I clear my throat and begin: “Herein is the recorded history of Christine Pizan, second daughter of Raphael and Risolda Pizan.” I think briefly of my dead parents, my dead husband, my dead friends and neighbors and all the people who peopled my childhood on Earth. Then I think of the crowd of clotted milk we’ve got left existing up here in CIEL. Briefly I want to vomit or cry.

My skin is . . . Siberian. Bleak and stinging. The faint burn of the astringent reminds me that I still have nerve endings. The tang in my nostrils reminds me that I still have sensory stimulation, and the data traveling to my brain reminds me that my synapses are firing yet. Still human, I guess.

The fern and I trade glances. What a pair—an intellectual who’s seen too much and a too-cloned plant. What fruitless survival. But after many years, I have finally arrived at a raison d’être. To tease a story from within so-called history. To use my body and art to do it. To raise words, to raise lives. And to resurrect a killing scene.

My nipples harden in the cool, dim room. Before me on the table, the tools of my trade, grafting, buzz to life. My torso, its virgin expanse flecked with goose bumps. The exquisitely small beauty of this reaction. Will goose bumps ever leave us?

In the mirror, I look into my eyes and begin my demonstration.

“Whatever you do, never use a strike branding instrument larger than a handheld wrench. Skin type is profoundly important; so are the depth of the cut, and how the wounds are treated while healing. Scars tend to spread when they heal. Electrocautery devices are infinitely preferable to strike branding.”

I mean to instruct.

I bring a handheld blowtorch to the head of a small branding glien.

“If you mean merely to make a symbol, a simple act of representation, multistrike branding is preferable to strike branding; you will have more flexibility and be able to give the illusion, at least, of style. For example, to get a V shape, it’s preferable to use two distinct lines rather than a single, V-shaped piece of metal. But if what you want involves intricate design, ornate shapes, the curves and dips of lines, syntax, diction, electrocautery is the obvious choice.” I pick up the electrocautery device. “So much like what used to be a pen . . .” I whisper, “only bolder.” I hold up my arms to show the variety of symbols: Hebrew, Native American, Arab, Sanskrit, Asian, mathematical and scientific.

“See? This is pi.”

My beautiful butterfly wings—adorned and phenomenal. I have reserved self-branding for hidden parts of my body. Until now.

I make my first marks. “Burning epidermis gives off a charcoal-like smell.” I pause a moment, at my reflection. Though we’ve all gotten used to the new look of ourselves, let’s face it: we are an ugly lot aloft in CIEL. Hairlessness happened first, then the loss of pigmentation. CIEL has presented humanity with new bodies: armies of marble-white sculptures. But nowhere near as beautiful as those from antiquity. Perhaps the geocatastrophe, perhaps one of the early viruses, perhaps errors in the construction of our environment, perhaps just karma for killing the natural world, did this to our bodies. I’ve wondered lately what’s next. What is beyond whiteness? Will we become translucent, next? No one on Earth was ever literally white. But that construct kept race and class wars and myths alive. Up here we are truly, dully white. Like the albumen of an egg.

I focus on my labor.

“Though it is technically possible to use a medical laser for scarification, this technique involves not an actual laser, but rather an electrosurgical pen that uses electricity to cut and cauterize the skin, similar to the way an arc welder used to work. Electric sparks jump from the handheld pen of the device to the skin, vaporizing it.”

I pick up my electrosurgical pen. I have become accustomed to not flinching, not grimacing, not displaying any physical response to the strange pain of it. What is pain compared to the cessation of lifestory.

“This is a more precise form of scarification, because it allows the artist to control the depth and nature of the damage being done to the skin. With traditional direct branding, heat is transferred to the tissues surrounding the brand, burning and damaging them. Electrosurgical branding, in contrast, vaporizes the skin so quickly and precisely that it creates little to no damage to the surrounding skin. You see?”

The skin near my collarbone screams. Tiny reddened hieroglyphics speckle my chest.

In a few hours, I will have completed a first stanza across the canvas of my breastplate.

“This reduces the pain and hastens the healing after the scarification is complete.”

I’m no longer sure exactly what the word pain means.

Everything in a life has more than one story layer. Like skin does: epidermis, dermis, subcutaneous or hypodermis. My history has a subtext.

“I first attracted attention in CIEL when I questioned the literary merit of a highly regarded author of narrative grafts—our now dictatorial leader, Jean de Men.”

I pause. “Hold.” The names of things. They betray our stupidity. CIEL, on Earth, was the name for an international environmental organization, but also for a young person’s video game before the Wars, before the great geological cataclysm. I remember. Now it’s what we call our floating world. What lame gods we’ve made.

And Jean de Men. I always found that name hilarious: John of men. He wrote what was considered the most famous CIEL narrative graft of our time. Which somehow became hailed, by consensus, as the greatest text of all time. As if time worked that way. As if earth’s history and everything in it had evaporated.

My head hurts.

As the

trace of song in my brain returns in orchestral bursts to taunt me, I stride like an impatient warrior to my treasure chest, filled with the last of Earth-based items I could not part with. I shove the chest aside—for the real treasure is beneath it, secreted away in the floor in a storage hole that opens only at my voice.

Within, a plain cardboard box. Which is not nothing: in a paperless existence, cardboard is like . . . what? Oil. Gold. I open it, and dig through its contents—CDs, videos, other ancient recording media artifacts—as if my hands are anxious spiders. I know the object I want better than I know my own hand: a scuffed-up thumb drive. I hold the thumb drive near my jugular. Our necks, our temples, our ears, our eyes, all have data points to interface with media. Implants and nanotechnology lodged exclusively in our heads, pushing thought out, fluttering and alive near the surface of our skin.

My room ignites with holographic projections: fragments of Jean de Men’s evolution. It’s a perfect and terrifying consumer culture history, really. His early life as a self-help guru, his astral rise as an author revered by millions worldwide, then overtaking television—that puny propaganda device on Earth—and finally, the seemingly unthinkable, as media became a manifested room in your home, he overtook lives, his performances increasingly more violent in form. His is a journey from opportunistic showman, to worshipped celebrity, to billionaire, to fascistic power monger. What was left? When the Wars broke out, his transformation to sadistic military leader came as no surprise.

We are what happens when the seemingly unthinkable celebrity rises to power.

Our existence makes my eyes hurt.

People are forever thinking that the unthinkable can’t happen. If it doesn’t exist in thought, then it can’t exist in life. And then, in the blink of an eye, in a moment of danger, a figure who takes power from our weak desires and failures emerges like a rib from sand. Jean de Men. Some strange combination of a military dictator and a spiritual charlatan. A war-hungry mountebank. How stupidly we believe in our petty evolutions. Yet another case of something shiny that entertained us and then devoured us. We consume and become exactly what we create. In all times.

The Small Backs of Children

The Small Backs of Children The Chronology of Water

The Chronology of Water Dora: A Headcase

Dora: A Headcase The Book of Joan

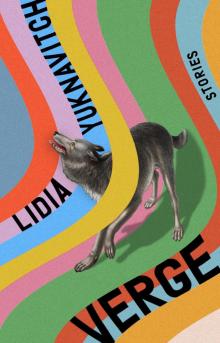

The Book of Joan Verge

Verge