- Home

- Lidia Yuknavitch

Verge Page 12

Verge Read online

Page 12

Wash off the excess foam, squeeze aloe and rub briskly between the palms, ahh, warm caress up and down the legs.

Slide the hand in each leg, spread fingers wide, and examine for runs, point one toe and enter the hose, pull slowly up the ankle, the calf, and over the knee to the thigh, pause; same with the other leg, pause; scrunch it inch by inch up the thighs to the balls pushed back up into the cave, to the penis tucked tight between the legs and secured with a thong and over the hip bones and snap the elastic around the waist with thumbs.

Then the pumps and the jewels: red stilettos and rhinestones in the ears, at the neck, and of course on the wrists.

HOW TO LOSE AN I

Do not rub from the nose toward the side of your face. Always wipe toward the nose in a horizontal direction.

* * *

• • •

HIS EYES ARE CLOSED. Wait, no. His eye. Just the one now. He picks up the phone. He dials. His skin is too hot against the headpiece. A woman’s voice says, “Hello,” then he speaks, then she says, “Jackson?” This voice resting him. His heart beating out thank god thank god thank god. She says, “Where are you?” He responds, “Can I see you tonight?” Then he nearly passes out.

He does not know how to explain why he needs to be in the car. He thinks up a hundred absurd errands a day so that he can drive around until dark. Maybe he needs that movement to hold him in place. When he sits inside at home, even the air looks empty. The whole world looks slightly off. As the change is not within him at all, but instead the world has changed its angle of vision, closed in on itself, defocused. Isn’t that the damnedest thing? Perhaps the line of a road is the only thing that will ever make sense to him again.

It makes him horny to drive to Mary’s house. They have never been lovers. They will never be lovers. He doesn’t fuck women. Not that he hasn’t, just that he doesn’t. Mary makes him horny because their way of knowing each other has lasted twenty years. She is a big woman, Amazonian, manlike except that this makes her unusually feminine, in a European way. Because she gives him back rubs that last two days. Because she can’t cook and he cooks for her and it makes her cry to eat. Because they are both neck-deep in their lives and have no idea how to proceed. Because they both ended up in California after swearing not to. Because she will not leave him, ever, did not, in the hospital, slept in a chair, like a woman waiting in a movie. Because she has little scars all over her body from a car accident years ago, little glowing white feathers covering her torso. Because their suffering is stronger than love. Because she will look him in the eye. Because she is the only human he has seen in months who will do that.

* * *

• • •

THE ORB ITSELF has no surrounding connective tissue. A CONFORMER made of silicone is placed inside the socket following surgery to maintain orbit volume and to help form cul-de-sacs or lid pockets that will hold the eye in place.

* * *

• • •

HIS DRIVING DOWN her dead end, his hearing the car door shut whack, his feet carrying him down a path he could walk with his eyes closed, his knocking on her door, her letting him in, their kissing, their looking at each other, smiling, then her eyes traveling down his body, then her saying, “My God, look at that!” Their laughing their heads off.

Their eating the pesto and pasta he cooks. Their getting high after dinner and his taking his patch off. Her fingers soft as whispers, his flesh hollow. Their watching videos until three a.m.—Red, White, Blue—and then their falling asleep, tangled bodies on the couch. Her saving his life, him saving hers, and no one else seeing it.

* * *

• • •

THE COLORED SPOT goes up, under the upper lid upon insertion.

* * *

• • •

HE DOESN’T WANT to lose his way. That’s why he bought the maps. Six of them, just in case technology fails him. Funny—each one is slightly different from the others. How can that be? You’d think there’d be some kind of consistency, some standard. But he finds a street on one and not another. He finds a bridge on one and not another. He finds sites listed on one and not another.

He’d bought the maps as part of The Plan. The Plan was to drive cross-country, to get back his mojo, his self-worth, to get in the car and reclaim his goddamn self. Mary had heard from her therapist that “healing journeys” were important, and she was going on and on about a possible trip to Europe, and he spit out, “What about a road trip? What if I took myself on a road trip?” And Mary had said, “That’s pretty loaded, Jackson. You sure about being in a car for something like that? Stuck in a car for that long?” And he’d said, “I love cars. I love road trips. I’ve always felt more myself when I’m driving—when I’m inside that movement.” She paused a moment, then said, “Maybe that’s just right. Maybe revising the story in a ritual like that, like driving, would be just the thing.” Then she’d looked him in the eye and said, “Go.”

The Plan was for him to drive from Seattle to California to Arizona to New Mexico to Texas, through the rest of those southern states, all the way to Key West. To drive it without stopping and capture it on film, a frame at a time, to replace the nightmare with something real. In a car not the car that had killed Michael, not the car that had taken his eye, but a new car he would get now. Beyond any of that.

* * *

• • •

AFTER YOU WASH and rinse your hands, lift the upper lid with the thumb or forefinger of one hand. Next, slide under the upper lid and, while holding the prosthetic in place, pull down on the lower lid.

* * *

• • •

WAKING UP IN THE NIGHT, cold sweat, like a big fleshy cliché of a self. Did his whole life leak out of the socket that night, or only part of it? His memory bends in on itself like a video stuck on pause. Even when he shuts his eyes as tight as possible, the images continue, perhaps stronger than ever, sometimes so fast he can’t watch, can’t breathe.

In the morning he makes a list of things to pack, even as his mind races ahead:

Boxers ten, jeans four, T-shirts ten, socks ten; sweaters and fleece three, leather jacket one, sunglasses brooks brothers, button-downs gap, running shorts nike, caps two; aftershave, deodorant, electric razor, beard and nose attachments, toothbrush, toothpaste, travel-size baby shampoo, l’occitane conditioner, lotion and bath milk, first aid kit, q-tips; water, scotch single malt five bottles, money, camera, film, eyes.

In the afternoon he packs the car. Mary comes over to help, and afterward, as she waves good-bye from her car, he thinks, She looks like a bird, some great prehistoric bird dipping its wing before taking flight.

In the evening, when it’s cool and the road whispers its blue-black beg, he drives.

* * *

• • •

DO NOT BE alarmed by tears and secretions. Simply wipe toward the nose with a tissue or warm washcloth. You can also use Johnson’s baby shampoo and Q-tips for cleaning dried secretions from the margins. If thick secretions or excessive tearing occur, call the emergency hotline.

* * *

• • •

YES, WITHIN MOTION is the only place he feels normal. Driving is best, next to that, swimming. There is something about the way a car holds you, about shutting the doors and the seat cupping you like a hand and the steering wheel presenting itself to you as if you could control things like direction and speed. Speed comforts him too, as if it were all of existence reduced to one element, a fundamental feature of existence.

With water it is floating. The way water carries a body. Weightless.

At first the road trip is like a photo essay. He keeps having simple feelings: Now I am crossing the border between Washington and Oregon. Now I am on the Coast Road. Now I am changing speed zones, highway to suburban area to city and out and up and faster again. He keeps having feelings like: I’m passing the same landscape for the second, third, fo

urth, fifth time. At first he sees only small changes. Then geographic ones, the hills a bit more browned from the sun, the trees less evergreen and more eucalyptus or palm. Smells seem more telling. He is driving, and California has a smell, orange trees and asphalt. He is driving, and the hills give way to ocean, sea air, and exhaust. He is driving, and memory moves his sight, his hearing, his heart beating.

As he leaves the West Coast, the windshield is a giant body—no, it’s just the California hills giving way into the Southwest desert, like great shoulders or the well of the small of a back.

But the body filling the windshield before him is always the same. No matter what he stops to take pictures of, all he hears is the clicking of the camera—no phones for him, he loves his solid old camera, the way film looks—its eye blinking machinelike, its shutter putting boundaries on light and speed. No matter the shot—red earth of New Mexico, redwoods of California, road signs and vistas, moonlight on ocean—all he sees is Michael thrown from the car, his shirt ripped open, biceps and chest cut clean through, Michael perfect, Michael perfectly still, Michael shot from the car onto the road, eyes open for the rest of his life.

During the drive, he realizes that the film he’s using has pictures already burned onto it. You know how it happens: camera gets left sitting around dormant, film gets developed, time is suddenly out of whack, and suddenly Christmas comes up against summer, the new entertainment center against the black-tie event. Driving past image after image, he is seized with the memory—a fact, clear and cutting—that somewhere on this roll are pictures of Michael.

His mind numbs itself. He considers blinding the camera with his fist. He considers throwing it out the window. He ends up putting it between his legs, its lens pointed up to him, its glass eyeing him questioningly.

He wakes up in a hotel crying, his tears salty and damp. His eye still cries—what is he supposed to think of that? He just lies there in the dark thinking, I am not blind. He isn’t exactly thankful, just observing. He looks at the objects in the room, like shadows of themselves in the dark: A chair. His bags. The television. He grabs the remote and clicks, holds the remote to his dead eye without thinking. He rubs it over the hole without thinking. He touches it to his mouth without thinking. He falls asleep with the little electronic gizmo clenched close to his cheek.

He wakes in a hotel in Tucumcari, bolt upright, tight like a car jack, teeth clenched. His eyes are closed, but he can still see the flashing red lights of the ambulance, or the fire truck, or the cop car, or all of them, or just retinal splashes gone berserk, or blood in his eye, or how the hell should he know?

He wakes up in a hotel in Pensacola. He’s left the window open all night so that he could hear the sea. He is smiling a little. He gets up to pee, pees, looks in the bathroom mirror. Mild nausea. He looks down at his eye in a hotel glass filled with saline solution. It looks back. His chest tightens; he does a breathing exercise until it loosens again. He leaves the bathroom, turns off the light, leaves the eye submerged and displaced.

* * *

• • •

TOO MUCH HANDLING can cause socket irritation.

* * *

• • •

A FRIEND HAD TOLD THEM about an oyster bar called One-Legged Pete’s. They should go there, he said, for the view, for the scene, and for these big buckets of crab legs that suck so sweet your lips ache. All those double entendres that used to be playful and sexy lodge in his jaw like nails now. He gathers up the pictures he has taken so far, his camera, and his wallet. Then he goes back into the bathroom and rips off two inches of white surgical tape. He places it where his eye should be.

* * *

• • •

IT IS NOT NECESSARY for you to wear a bandage.

* * *

• • •

AT THE BAR he thinks how right the friend was. He thinks how much Michael would have liked it, Michael the more outgoing one, the more playful one, the one with the GQ smile, Michael the already tanned don’t need to go to fucking Florida one, Michael the well-hung, the fucking god in bed, the one who never cried. Blue eyes. Two. Perfect as water. He looks out at the ocean, pictures them swimming in it.

At the bar he takes his pictures out. He looks at them closely, one at a time. Whatwhatwhat has he been taking pictures of? Things anyone could see from a moving vehicle: Road signs, big farm fields, lines of trees. Shots of hills garroted by telephone wires. Images of strip malls and gas stations and truck stops. One in particular baffles him: license plates, for Christ’s sake. V19 GBD, New Jersey. PLC 306, Colorado. 1AFB228, California. HOT ROD, Nevada. Is HOT ROD why he took the picture? Was he drunk? He doesn’t remember. He does remember a conversation they had, about how lucky they were—that neither of them was sick, or likely to be; that both had been careful and precise sexual partners before they got together; that both were young and ready to commit and make a life together stretching out like the fingers of a human hand. He is seized in the gullet. He cannot order a bucket of crab legs. He wants to wade into the sea up to his eyes and cry.

* * *

• • •

MAKE CERTAIN TO USE all the medications prescribed to you.

* * *

• • •

THOUGH HE HAS CONSIDERED turning back every single day since he left, just as he has considered suiciding every single day since the accident, he keeps going, and a day comes when he reaches Key West. The heat of Florida has dulled his senses. The taste of scotch is permanent inside his mouth; he can taste it anytime he presses his tongue against his inner cheek. He checks in to a beautiful white hotel named the Conch House. The linens smell heavily of fabric softener in a way that comforts him. The walls are white. The furniture is white. Everything is clean like brushed teeth or sheets.

He sits out on the pool deck in a white wicker chair. A hotel attendant brings him a piña colada. He spikes it further with scotch. It tastes like shit, but he doesn’t care; he is relaxed and drowsy, his eyelids are heavy with almost-sleep. He is wearing his eye. His camera is in his lap. He has in mind a short nap and then, as the sun sets, a walk down the main drag for photos. Breathing in the thick wet heavy of Key West, he comes close to dozing.

An enormous splash snaps his lids up, to reveal a beautiful blurry sea creature; no, a statue fallen into the pool; no, a young man tanned and slippery surfacing from a dive. His hair is black and sheened as a record album. His skin the color of Albuquerque sand. His eyes unbearably onyx and open. If there is something that Jackson does not want a photo of, an image of, it is this young man. If ever something could be violently true of his life, it is that a photo of this young man might kill him. Even taking the picture would be like being shot in the face. He is overcome with this feeling. It is horrible, this beauty. He begins to cry, and soon he is weeping uncontrollably. Worse, the young man sees him and begins to move toward him. As he comes closer and closer, till he’s as large as a cinematic close-up, his lips torturously full, even the bridge of his nose excruciatingly perfect, he begins to surrender. His skin goes slack, and his jaw gaws some, and his heart stops jackknifing, and it is then that his camera slips to the concrete with a little cracking tink.

“Oh, man, you dropped your camera,” the young man says. “I hope it’s not damaged. Lemme wipe my hands off. . . . There. Let’s have a look at it.”

He turns it over and over in his large hands like a sunken treasure.

“Oh, Jesus. I think the lens is cracked. That’s terrible. Those can be expensive to replace. Stay here—I’ll go ask up front if they know of a repair shop. I’m sure they can find you one.”

The lens is glass. Old-school.

And with that the young man and his camera are both gone.

* * *

• • •

IF TOO MUCH TIME passes before fitting, the socket may begin to shrink and it may become more difficult to achieve a satisfactory cosmetic and functional r

esult. If too little time elapses, not enough healing has occurred to achieve a proper fit.

* * *

• • •

BACK IN HIS HOTEL ROOM, he locks the door. He shuts the drapes. He turns off the light. He doesn’t ever want to see the boy again. He doesn’t want his camera to exist. He hopes it spontaneously combusts. He’d rather die than open the door to the knocking brown hand of the beautiful young man holding the idiotic and horrible camera out to him, saying, There, I had it fixed, it works like new, now you can take all the photos you want while you’re here, and would you like to have a drink to celebrate, the hotel has a bar, maybe dinner if you’re free, if not that’s fine, just thought some company might be nice tonight, and where did you say you were from? He catches himself looking at the back wall of his hotel room for a way out, but all he sees is the mirror.

What was he thinking? He wasn’t ready for a trip like this. He wasn’t ready for human interaction. He is suddenly surprised he’s made it this far without another crash. He pours himself a drink, sucks it down, then reaches up and pry-sucks his eye out of its socket. It tumbles to the carpet. He picks it up and puts it in his mouth. He considers swallowing it.

What it comes down to is this: He feels trapped inside this white room with a dead eye and a self he cannot bear and a set of memories more alive than his present. He feels as if the kind man will come back to kill him at any moment. He feels as if there is no escape. He thinks, I will die here one way or another. He picks up the phone and calls Mary, gets her machine—Mary, Mary, I’m lost, I’m drunk, I’m tired—I don’t know how to do this. He realizes how in crisis he sounds. He sends her a hundred texts saying some version of I’m fine. It’s fine. You know how dramatic I can get in hotel rooms. Everything okay. All good.

The Small Backs of Children

The Small Backs of Children The Chronology of Water

The Chronology of Water Dora: A Headcase

Dora: A Headcase The Book of Joan

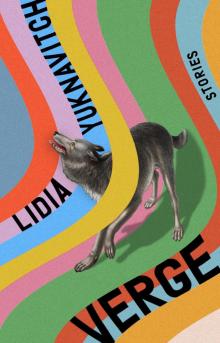

The Book of Joan Verge

Verge