- Home

- Lidia Yuknavitch

Verge Page 6

Verge Read online

Page 6

When he awoke late the next morning, he had not a hangover but a clarity of vision as sharp as a diamond lodged in the center of a skull. He understood with full force the error he had made, with his little city on the table, with his lack of drive, with his life. He saw with bright white light that his entire existence had been leading up to a single moment, that he’d very nearly blinked and missed it, the way we often do in our lives, droning along in what’s ordinary and familiar, missing the moment at hand even when everything in the universe is pointing the way toward sight. He saw that his superficial efforts with refuse were the key, that decay itself was the giver of life, the secret of the universe, the place from which all stars collapse and all systems tower and all logic gets born and then falls.

He’d simply mistaken the act for the thing itself.

He stared at the darkening, shrivel-skinned arm. He poured himself another cocktail and drank. Still coughing, he headed back to his city, thinking of all the death it takes for life to flourish.

He laid himself down on the dining room table alongside the new city, his arm next to the dead one, and thought of all the teenagers in the Destination Sky Planetarium, seething and coupling, and he cradled the arm, slightly blue and stiff, in the crux of his own, and he closed his eyes to the world and readied himself, not for sleep but for alchemy—for the shifting of molecules, the transmutation from solid to another form, from metal to gold, or liquid, or the speed of light itself.

SECOND LANGUAGE

Sometimes she understood herself, in this new place, as a body inside out. A body no longer contained, leaking meanings. She tucked in the corners of her face and went back out into the world, knowing that the bloodstreaks in the street behind her would repulse at least some bystanders.

The blue veins standing out in her neck and at her temples made her look eerily like a map of Siberia. Even though in this place she knew that the word “Siberia” did not signify, somehow she took comfort in the Siberian look of her neck and temple veins; just thinking of it made her walk with a slightly straighter spine, a girl of the North. Though some people she passed looked at her with a kind of disaffected latte pity, it made a lot of sense to her. Her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother had been Lithuanian, had survived winters, had been sold to Russians, had died in white and cold and poverty, and so a vast white expanse with rivulets of black and blue was a concept she understood. Didn’t land look that way to birds on great journeys? Birds had outlived the Ice Age. Perhaps my body is like a place seen from the sky, she thought. She looked up. Then she returned her gaze to the faces of this American city.

She had a vague understanding that her insides were visible on the outside—and how unfamiliar that appeared—but what were exposed capillaries and dangling entrails compared to the wallets of businessmen jutting from the asses of their fine suits, or the violently painted lips of women whose hairstyles and manicures rivaled their mortgage payments?

She looked up. Gray sky, gray buildings. Concrete with wind. At least there were trees here. Trees never lie. But where in the world, she wondered, were the graywolves?

Pulsing outward, she made her way to the front man whose address she’d been given when she arrived, after crossing over from Canada in a white-painted popsicle truck. Girls like popsicles driven over stitched borders between nations. Apparently this kind of front man did not regard an inside-out girl as unusual or damaged. “Are you at least a C cup?” the man on the phone had asked. She still had her use value in this place, is what she understood him to mean. Her heart hidden behind the new pillows of her adolescence.

The front man lived near a freeway—what freedom was it meant to have?—in a snot-colored two-story house with black plastic in the windows where curtains should be. When she knocked on the door, her throat cords braided and her vertebrae clattered. The man who answered the door looked to be in his late teens. Older than her. Inside were more girl popsicles, most of them around twelve or thirteen by the look of it. One might have been fourteen, but height wasn’t necessarily a sign of age. At least two of them looked young enough to need mothers. She stared at the melting popsicles, her kin, all of them with too-thin, too-white wrists wound with bulging blue rivulets. But the television in the living room bombarded her senses with image and sound in waves. She bit down on her tongue enough to feel it.

Good blood in a mouth. A warm that delivers you, that returns you.

Days went by, enough to create time.

She ate.

Slept.

And in the evenings, every evening, she was delivered to some new address.

Each address had an old gray man billionaire with money enough for a girl’s body and threat enough to take her life.

The pretend pretty of the Portland city all around her days: disposable cartons and plastic and paper and coffeecoffeecoffee and black clothes and bike lanes and funny little hats and eating and driving and thousands of kinds of potato chips. Whole aisles at grocery stores devoted to potato chips, salty ones and square ones, greenblueyellowred ones, chips with pepper and chips with vinegar and some with “bar b q” flavor, red with salty dye. Coffee spilling from the mouths of hundreds of shops and beerbeerbeer everywhere and strip clubs outnumbering McDonald’s. She wondered if all these regular well-dressed people walking around like Bic lighters had been to the strip clubs or if she was the only one. If they did go, were they the same after? Her emotional circuitry was interrupted every time she took off her clothes.

Of the land in this Portland, there were mountains, and she remembered that terrain could still overtake human lives. She wished she could hear their stories, but she couldn’t from where she was, boxed here.

She saw the lively mouths and freshly sculpted bodies and the surface sheen of the people in this city, she saw their righteous bicycling circles and their coffee corners and the neon signage and the stutter of bridges over incarcerated rivers. Still, even walking the sidewalks, smelling the pee and rotting food mixed with car exhaust and wet leaves and dirt, she could see that money and consumption were what the place was made of. Everyone seemed to be worth so much. How did they wear their I’s so easily?

Sometimes while walking, she witnessed animal behavior: blue jays adopting different languages, gardener snakes S-gliding over concrete into their shrub havens. The cacophony of frogs under overpasses near streams or gutters. Walking nowhere reflected back to her a sense of nonbeing she could live with. Sometimes she stopped to sit in the dirt, and an old beer would tumble by. Coors, it said.

She considered trying to speak to other mammals. But her voice locked in her throat when she thought of what she was: a girl with nothing, no money, no family, a name without documents. All she could feel was the warm cave between her legs and the small and sure soft swell of each of her breasts. Well, at least my body has meaning, she thought. Value signifies meaning, right?

In the evenings, when she was delivered like a cardboard box from a UPS truck, sifted through by rummaging hands like recycling, she went dead.

Her nightly destinations threatened to unweave her intestines and pour them out in a gray mucous line onto the street. Somewhere in her skull or rib cage, the hint of old ideas—family, home—lingered, but the memories were not strong enough to negate their absence in this place. In this place her being was her bodyworth. In this place it was be or die.

This night, like every other, the doorway to the hotel looked to her like the yawning mouth of an old man. Repetition makes a thing real. The everynight of things entering a body until a path was carved.

Her eyeballs shivered, and her rib cage made a sound in the wind like chimes. Knocking on the door took more than a girl.

Well, she thought, even if I am entering the loose-skinned mouth of a saggy old man, a job’s a job. A phrase she’d lifted from the mouths of other popsicles as a survival mantra. Along with this: Do not do not do not behave “like an immigrant.” Do

not out yourself. Language is a funny thing, she thought. It opens and closes. It trips you like a crack in the sidewalk. Keep moving or die.

On the television in the hotel bedroom of the slackened old gray man—her john for the evening—was a war zone. Between the old gray john’s legs she could see the televised rubble, the huddled clumps of human crouched and lurching and running. “Suck,” he said. Deflated bad-tasting balloons filled the wet opening of her mouth. The rubble and the humans and the CNN ticker tape . . . she closed her eyes and sucked. He fingered into her. He put his jowls down near her face, his mouth to her ear: “I’m a very important man . . . the most important man. . . . Your little holes are so tight.” He smiled wide enough for her to see the pink of his receding gums.

There was one thing besides her body that she possessed—a story, in a foreign tongue but still a story—and always upon her return to the front man’s concrete house she would relate the story to the other popsicles. She did not know why she retold it, only that the recitation could not be stopped. What else did she have? What currency but story? Like the continual expulsion of her insides to the outside, story came. And the popsicles would lean in, eyes wide, mouths and wrists open to the future, and listen.

Long ago in a faraway land, there was a czar who had a magnificent orchard, an orchard second to none. However, every night a firebird would swoop down on the czar’s best apple tree and fly away with a few golden apples. The czar ordered each of his three sons to catch that firebird alive and bring it to him.

The two elder brothers fell asleep while watching. The youngest son, Ivan, saw the firebird and grabbed it by the tail, but the bird managed to wriggle out of Ivan’s grasp, leaving him only a bright red tail feather.

Ivan, assisted by a graywolf who killed his horse and then felt sorry for him, because even wolves understand how unfortunate men are, managed to get not only the firebird but also a wonderful horse and a princess named Elena the Fair. When they came to the border of Ivan’s father’s kingdom, Ivan and Elena stopped to rest. While they were sleeping, Ivan’s two older brothers, returning from their unsuccessful quest, came across the two and killed Ivan, threatening Elena to do the same to her if she told what had happened. They ravaged Elena and threatened to cut out her tongue.

Ivan lay dead for thirty days until the graywolf revived him with water of death and water of life. Ivan came to his home palace at the wedding day of Elena the Fair and one of Ivan’s brothers. The czar asked for an explanation, and Elena, with the wolf standing guard gnashing his teeth, told him the truth. The czar was furious and threw the elder brothers into prison. The wolf ate their entrails out in the night. Ivan and Elena the Fair married, inherited the kingdom, and lived happily ever after.

None of the popsicles ever said a word about the story. But her telling brought sleep lapping over them like a kind night ritual.

* * *

• • •

TIME PASSED. Enough for her to realize no graywolves would come.

Although she knew that stories had beginnings, middles, and ends, she also knew that, for her and those displaced like her, the order was out of whack. Once story had been like home, but now story had been fragmented and gnawed at the edges. Once there were heroes and saviors, but they had turned into con artists and reality-TV stars and dizzy whirring consumers. Or maybe there had never been any heroes and saviors and those stories were only meant to trick girls into forgetting how to be animals.

Just as it lengthened her spine, strength in a girl like her made her eyes smaller and steelier, her jaw more square, her cheekbones high like canted clamshells. Even her collarbone spoke, but in this place people didn’t seem to hear. They responded with dead stares or shrugged shoulders.

You need to speak better English, they said.

She longed for the graywolves, furred and growling and teethed, to rip loose the entrails of enemies.

The last night, in the hours before dawn, after she was delivered back to the house of ravaged popsicles, after she had again told the story from her mother dead, her grandmother dead, her great-grandmother dead, after she had washed the blood from her mouth, her nipples, from between her legs where she realized life would never pass the way it had moved from the cleft of her mother, her grandmother, her great-grandmother, and the blood from the smaller aperture of her ass, the rivulets of red winding their way down the rusted drain holes of an unclean shower, when she put herself down on a formless mattress on the floor under a window of the house filled with girl popsicles, the cave of her concrete world opened up—cracks in reality—and through the window she could see the towering white-eyed angels hovering over them, streetlights, they called them here, and a nightwatch of lost leaves whispered against her hair. Tin and paper rustlings made urban lullabies. Or maybe it was just the ugly end of the city, like everyone kept saying on television, where girls go to disappear and die. She wondered if death could transform into an animal, by her own hand even. Not as an ending but as a bluewhitened pulsar; couldn’t it, blazing the entire night sky apart and atomizing everything ever done to girls? Couldn’t deranged graywolves come back from old stories, from native land, to tear out the throats and sagging balls of old gray johns; couldn’t they enter through astral projections ancient as folktales embedded in the dead bones of her mother and hers and hers, gone to dirt but still alive there—charged? Weren’t there still secret triumphs, secret powers, to living dead girls?

There were; she could feel it. The strength that lived in this popsicle house. She could feel it, and she had no word for it.

Without thinking, she punched a hole with her fist through the window in their cinder-block box. She elbowed the hole until it was big enough for the popsicles to leave, elbow blood everywhere; then, quiet as a mother’s voice singing a child to sleep in a mothertongue, they slipped out. As the popsicles tumbled out into the night like child refugees—oh! how they glowed like human snowflakes underneath the streetlights!—she knew what else to do. She’d have to conjure the graywolves. Not the old gray wrong American manwolves, but the real thing.

She took the broken pieces of window glass and gutted herself so that her entrails were finally fully free and right. They slithered out in vivid shades of girl onto the floor. Someone must stay behind to help the dream come true.

And it did, for only then did the real graywolves smell it—her entrails, animal and good—and they came down from the mountains one, two, three, four, ten, twenty, and entered the cinder-block house and ripped the throats from the wrongheaded men and tore them limb from limb, and the wolves’ teeth and howls reminded everyone everywhere how there is something from spine and ice that has yet to form a language, a yet-unfinished sentence, one those bought-and-sold Eastern European girls are learning besides English: They are learning to gut themselves open so that others will run.

I tell you, do not go near that place. Do not go near it. Graywolves guard the ground there. Girls are growing from guts, enough for a body and a language all the way out of this world.

A WOMAN SIGNIFYING

You don’t see cast-iron radiators much anymore, the old-fashioned kind. People have learned to be careful around them. But her building was old. She stared at the radiator’s vertical lines and thought about old obsolete things. She took a deep breath, then touched her cheek to the radiator for three long seconds. It was a perfectly calm gesture, seemingly disaffected but deliberate all the same. “One, two, three,” she said, breathing out with each word. One, two three: The heat singed silent through the layers of her skin, through the fleshy part of her cheek.

When she had finally thought of it, how proud she’d been. It had happened in the time it takes to scald a wrist cooking bacon. They’d been standing in the kitchen, she’d been making them breakfast, he’d said, “I’ll be working late again tonight, don’t wait up for me,” and she could feel her own ass sag, her love handles bulge, her chin develop a double; she could fee

l their sexlessness making mounds of her body like biscuits.

What patience she had! What brave, glorious, undaunted patience. And even then she had realized it would take patience—patience to sit in front of the hot metal, patience to draw her face near, and nearer even as the heat became evident, whispering toward her cheek. Patience at the moment itself, to do it right, to pull away slowly, for after all she did not want to rip half her face off and leave it staring back at her from the radiator. She wanted a controlled effort, a specific result. Only a wound, a perfect wound. She was absolutely confident at the idea, because what was this patience compared to her life? Three small seconds.

She winced or smiled as she peeled her cheek away. Burned, sweet flesh tickled her nostrils. Her eyes welled, swam in their little sockets. When she could see properly again, she rose and staggered, flesh screaming, from the living room to the kitchen.

The first thing she did was pour herself a glass of vodka. The kind of glass one might fill with milk. She drank it down until the heat in her throat and chest challenged the fire in her right cheek, the fire filling the right side of her face now, making her nostril flare a bit, her lip quiver, her eye close. The vodka streamed down the center of her body, a streak of high voltage.

She thought of things her women friends had said to her over their scripted lunches: consolation, advice, admonishment. Come on, be serious, get a grip. You don’t really hate him, do you? Grow up! Be sensible, have some self-control. Maybe go on a diet—herbs and tofu. You’ll feel better. Change your hair. Your perfume. Your heels. Make something of your life. Sex isn’t everything, don’t be ridiculous. You are obsessing. You are playing the victim. You’re just being lazy. I wish I had your problem!

Or: Honey, what you need is a good fuck.

How do you tell women who wear fake nails and baby powder between their legs and order chicken salads with vinaigrette at linen-covered tables and try desperately to chew without smudging their lipstick that women must keep moving or die?

The Small Backs of Children

The Small Backs of Children The Chronology of Water

The Chronology of Water Dora: A Headcase

Dora: A Headcase The Book of Joan

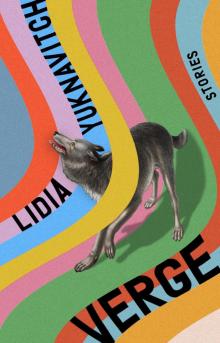

The Book of Joan Verge

Verge