- Home

- Lidia Yuknavitch

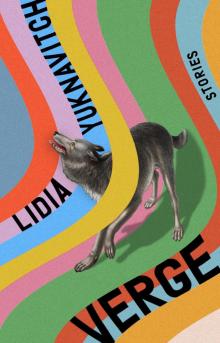

Verge Page 7

Verge Read online

Page 7

She walked around her living room holding her drink, feeling animated. Alive. Gesturing with her drink to the TV, the couch, the different objects in the room, yelling at everything and nothing.

“He’s not the only one who can play this game!” she shouted, confronting a lamp. “Fucker! Motherfucker!” She trudged back and forth across the carpet. “I hate you! I hate you! I’ve given you half of my life, you fucking bastard!” She brought the glass of vodka up to her mouth so hard it clanged against her teeth.

What advice was there for a woman’s epic anger when it was equaled in intensity only by need? The room swelled with shame and silence.

The now-cold pain in her cheek pierced straight through her skull. She thought maybe her right eye had swollen shut, or at any rate she could no longer open it. She went to the bathroom to have a look. On her way she realized this was all a little disgusting, the kind of story that would make the listener lean a little away from her. Not in public. Not so close. “Should we keep quiet?” she whispered to the bathroom door. “See where keeping quiet has gotten us.” Then she opened it and looked herself in the face.

That really is a beauty, she thought. The outer edge was deep red and crimped; a purplish welt rose on either side like mangled lips. In the center of that, a long, yellowish bubble of blistered skin like sea foam. An amazing wound. A well-thought-out, carefully executed wound. Kind of perfect.

By the time he gets home, she’ll be out already. By the time he gets home, she’ll have outlined her own eyes in black, added lashes in blue. By the time he gets home, she’ll be blushed and lipsticked, red as a Coca-Cola can. Push-up bra and Spanx. By the time he gets home, after she’s stared at the tools of the face for a long while, she’ll have decided on a gold-dust shadow, she’ll have traced a gleaming glow around the thing, ringed it in precious metal. By the time he gets home, she’ll be sitting in a bar with the most perfect wound imaginable. A symbol of it all, her face the word for it.

THE ELEVENTH COMMANDMENT

To this day I don’t know why she hung out with me. I was pitiful. Sickly, pale, booger-picking. Braces. Matted hair that argued with itself like crazy. The works. You can imagine: I was the kid who sat in those concrete tunnels by myself all during recess, who wet my pants during social studies in sixth grade. You heard right. Sixth grade. I had already developed several neuroses. I had the stress of a forty-eight-year-old man. Are you getting the picture? Sure you are. Everyone knew a kid like me.

The first time I met her, she came into one of those tunnels and sat down next to me without saying a word. For the whole recess. I didn’t say a word either. I was scared, but also weirdly thankful. She didn’t even look at me.

The next day she got in there with me again. Finally, toward the end of the forty-five minutes, she said, Chris Backstrom has hair around his pecker. That’s all. Then the bell rang and she ran out, and I sat there for a while longer considering this. Chris Backstrom had blond hair, so I tried to picture blond hair growing in beautiful curls around his penis. I shuddered and thought I might vomit. Then I got a splitting headache. I kept checking to see if my nose was bleeding. By the time I made it back to the classroom, I was near fainting with pain, and they sent me to the nurse’s office. After some time my mother picked me up, and I went home. She was very angry.

About a week later, the girl came back down and said she wanted to show me something. She said it was very important and that never in a million years would I get the chance again. Then she asked me if I wanted to see. My mouth was filled with saliva, and my palms were sweaty. I felt an uncontrollable urge to pick my nose; then I thought I might have to pee. I said yes in a wobbly little voice. I thought I might have gone cross-eyed there for a second.

She lifted up her skirt, and she pulled her panties down. This smell filled the concrete tunnel, and it was good but it was also terrifying, and I thought I could somehow taste it.

When I look back, I think of how she saved my life that day.

Her pussy had little red hairs on it, and she said, See, this is very rare. And she took my hand and we petted her together.

Later she coaxed me out of the tunnel, and we walked around to the far end of the field where the goalposts were. Some boys were playing soccer, and true as life the ball ended up clocking me upside the head. My face turned redder than humanly possible; I thought my skull might burst like an overripe fruit. I pictured it exploding there on the field, pictured how everyone would laugh, then stop and stare, stunned, confronting the death laid bare before them, the dull head of a boy in pieces at their feet.

The boys came toward us, and then I pictured another death, death by pulverization, death by soccer players cannibalizing me on the field. Food, I felt like: too-white food.

As always in grade school, they started to taunt me, ignoring her but drawing a tight circle around me until it felt like the oxygen was being sucked right out of my lungs. One of the leaders of the pack came up and stood over me, his chest puffing out, his great mouth opening and closing, his teeth drawing nearer, yelling and spraying spit, his breath hot and burning on my face. Finally his hand drew back and his body moved on me with the weight of an animal.

Then suddenly she was there, between us, stopping the turning of the world. She said, You know about the Eleventh Commandment, don’t you?

The guy tried to shove her aside, but she shouldered her way back in; she was taller than him, as is often the case at that age.

The Eleventh Commandment, she said again. It’s in this secret book that someone found in a clay pot. They kept all the secret stuff out of the real Bible because it scared people too much and it was too difficult for most people to understand. You had to have intelligence, but you also had to have imagination, and most people barely have the one and none of the other. Like you chuckleheads.

Baffled by this development, the gang of soccer players let the insult pass.

In the secret book there is an extra commandment, she went on, and it’s bigger and more serious than all the other ones, because it includes what will happen to you if you sin against it. Some boy to the side yelled out, You’re full of shit, there’s only one Bible, shut up you stupid bitch! She headed over to him, still talking, until her words were breath-close to his face. The reason you don’t know about it, dumbfuck, is that no one thinks you’re smart enough to get it. They don’t let just anyone in on it. You have to prove yourself. You have to show them you’re worthy, mature, that you can handle it. But I’m gonna tell you because you’re all too stupid to get that far, and I think it might save you some trouble later in life.

I don’t know how girls like that get the power to lead people. I don’t know what it was about her—she wasn’t pretty like the popular girls, and she wasn’t athletic either. It was more like she had this tiny bit of craziness that made people scared of her, but, like all disruption, it made you want to look, listen.

Some other schmuck called out, Well, how the hell did you hear about it, then?

Mary Shelley came to me in a dream and told me about it, she replied calmly.

Who the hell is that? the same guy said.

She took a deep breath and said, Mary Shelley, shit-for-brains, wrote Frankenstein, the greatest book of all time. If any of you idiots knew how to fucking read, you’d know that.

Then she made her way back over to me—me standing in a puddle of fear, airless, weightless, dizzy, already having surrendered, already having left my body to take my beating and accept it. Then, standing near me, she told the story of the Eleventh Commandment.

There was this leper, she said, who was friends with Jesus. Everybody was grossed out by him on account of his nastiness—his skin was all gray and full of pus, and he had these horrible open wounds and shit. He was actually a pretty nice guy, but no one wanted to go near him, and since most humans are ignorant, they translated their disgust of his skin to him, deciding he was dange

rous, deviant, and evil. But Jesus, being smart, really liked him. He even thought the skin thing was interesting—after all, the man’s suffering made him closer to God. Besides, Jesus had played chess and drunk and had great philosophical conversations with him, so he knew he was dope. It was just the town losers, who didn’t know shit, who hated him.

So one day this kid passed by the leper’s house and peeked inside the window and saw the leper and Jesus fucking. (At this point the crowd of boys began to hurl obscenities at her in disbelief.) I know, she went on, the town reacted exactly like you morons. But the fact was, Jesus and the leper were fucking. So the town, like you assholes, decided that Jesus was possessed by the leper-devil, that he was under some kind of leper-devil hex, and they set out to save him.

They were stupid, so their plan was stupid. They decided to wait for the leper to go to sleep and then burn him and his house to ash. But of course Jesus ended up in bed with the leper that night, and those idiots burned ’em both to ash.

Well, God was pretty pissed, as you can imagine. The next morning he cracked the sky open with lightning and put out the eye of the sun and threw down a rock slab bearing a new commandment. Thou shalt for the rest of time be stricken with disease, it said, when thou settest eyes upon the uncanny.

The minute they read that thing, all their dicks turned black and the pain of acid on flesh shriveled them up, and after a week or so their peckers dropped off altogether. And that’s what happens to anyone who rejects the uncanny without wondering what it means, without recognizing that they’re looking at a fucking miracle.

It was the strangest story we’d ever heard—strange because we didn’t know what “uncanny” meant, but also because she did, and because our little dicks were getting hard from this tall girl telling it to us. Strange because we hated anything about homos, because that’s what people called us when they wanted to beat us up, and strange because half of us were, or were on our way to becoming, what those beat-us-up boys hated—bodies that felt like home.

It’s not like they couldn’t have beaten the crap out of my sorry ass anyhow, or pushed her around, or played out their sadism in any number of other ways. But somehow by the end of her story, a little path leading off the field had cleared for us, and she walked it, and I followed her, and I got the impression that the waves would hold like that until the Romans turned to chase us, at which point they would be consumed by the sea, or perhaps just by all of their ignorance drowning them and washing them away.

DRIVE THROUGH

In your car. Your red Toyota Corolla. Exhaust hums in front of you, behind you. Small voices scratch out of giant boxes with writing on them. Drivers dig through pockets, ready their money. The sun dips down into her wallow; evening descends on a line of cars in the drive-thru at McDonald’s.

A tiny man in the distance. You can see him in the rearview, just above the words OBJECTS IN MIRROR ARE CLOSER THAN THEY APPEAR. He is on the move, window to window, car to car. In the rearview you can see the faces of other drivers pinch up as he nears their cars. They dread him. Already they are cringing, scrunching up their shoulders, locking their doors, working buttonholes with their asses in the vinyl seats, trying desperately to look at something else. Anything but the approaching man, bearded, hair knotted, slightly dirty, clothes rumpled and clearly week-worn. White male, thirty-five, maybe forty-five.

By the time you get to the young black man in the first window, huge waves of relief send a shiver up your back. You’ve made it, goddammit, and an angel has appeared to take your money. There is no room for the nasty white man begging money to come around to your driver’s-side window, he could never fit between the ledge of the window with the guardian angel and the safety of your car, your finger on the button to raise your window should danger appear. The young man takes your money and returns your change, asks you what kind of sauce you want, gives it to you in a beautiful little white bag with golden arches on it, why, it’s heaven, it’s just like being in heaven, the delight is filling your whole body now, earlier you thought you had to pee and the line of cars seemed unbearable, but now, now you are making an exchange that is simple and good and profound in its truth. The young man smiles and waves as you head slowly to the second window, his salary doesn’t even enter your mind, you are free, you are on the way to the second window.

Surely he is at one of the cars behind you. Surely things will get held up there, someone will refuse to open their window and he will knock on it, or he will appear inside the frame of the front windshield and the driver will avert her gaze, he will give up and move on, or back, or away. You risk a quick look in your rearview—nothing nothing nothing, like pennies from heaven.

Your car glides almost magically to the second window, its opening apparent, hands visible, a bag of food bulging and white and smelling of good oil—all vegetable oil—and fried things. Your family is waiting at home. Your car is filled with gas. Your money has been paid.

A pimply-faced girl with headgear and braces hands you your bag, and you see capitalism and youth emerging from the window, you see her first summer job, her first lessons at responsibility and a savings account and taking care of herself, you see her on her way to college, yes, that’s it, the summer before college, the lessons she is learning, what a good student she will make, how she will excel in school, how she will learn well, how she will enter the workforce with a good head on her shoulders. And then there is a rapping at your window on the passenger side, and strange how you forgot, isn’t it? And your head swivels over out of dumb instinct, and there he is, his bad teeth and leathery skin and marble-blurred eyes filling the window, like a close-up, magnified, terrifying. His horrible mouth is opening and closing, he is saying something to you, he is talking to you, his muffled voice breaking through the glass shelter, now he is yelling, you are clutching your bag for dear life, you are putting your car in drive, his fingers at the ledge of your world, your own body like a snake’s: all spine and nerve.

Then a new image: From the front window, you see a man in uniform, my God, an older man with a McDonald’s uniform complete with cap and manager’s badge is running toward your car, he is waving his arms, he is shouting. With one hand you are clutching your steering wheel as in a near-miss accident, and with the other hand you are clutching your white bag of food, heavy and full, and your eyes are like a frozen deer’s, and your body is taut, and your nipples are hard as little stones. Your mouth is dry, and you are as alert as you are capable of being. The manager yells at the shitty little begging white man, You go now! You go now! You outta here now! Shithead! Motherfucking! You go! No slaving here! His slip of the tongue doesn’t even faze you. You are with him. United. You are grateful. There is no dividing you. The two of you are in it together, you are saving each other, you are making the world a better place, you are the American way embodied, you are at each other’s back, you are two hundred billion served.

CUSP

There is nowhere a girl can go. The only runaway position is prostitution and that can kill you about as fast as a violent uncle or a crazy daddy.

—Dorothy Allison

This bed smells of my skin. If I roll from my back to my belly, sweat cools near my spine. If I close my eyes, I am like an animal up here in the heat and wood, baking in the daylight, my eyelids heavy, my thoughts slow and thudding. I am waiting for dark, for the release, for breathing to animate me. This room and everything in it brings me closer to myself: nocturnal.

From the frame of my attic window, I have imagined the inside-out of this town. Its heat rising from dust and scrub, its mindless longing for rain, its heart beating with dumb insistence. Outside my room the world has expanded and contracted like the tight little fist of a child. Years have gone by. I used to wonder who would want to live here, like this, some dried-out town at the edge of the story line, the nightly news, never quite making it into the picture, its people crowding the geography somehow without evolution or design

. There is a black-and-red sign over the door of the Texaco. It reads TEXAS, USA. No city. No need. That’s the whole deal, stuck up there on a piece of metal the size of a license plate. Like thought stopped for gas and died at the pump.

I remember the day I moved from my room downstairs up to the attic. It had been my brother’s. He’d gone to college, I’d hit puberty, the two motions crackling away from each other like electrical currents. The white canopy bed of a girl died that day, for I never went back. The day I moved into my brother’s attic room, I felt the wooden walls close in around me, as if a second body were there to hold me. The wood grain looked to me like dark, warm skin, comforting me.

Underneath the bed I found artifacts from my brother’s life. Empty bottles and broken glass, trash, foil, used rubbers and tissues, tiny vials and a stretch of surgical tubing. It was a year before I found any needles, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. He’d shown me his world when I was around ten, knowing I would love it as I loved every moment he let me be in his attic, adoring him, adoring the dark of the room, the broken rules, the thick unbearable silence, the smells I hadn’t names for, the dizzy swell of skin making sweat. But I did find everything. A loose board in the wall, a stash I only barely comprehended at the time. Wasn’t I meant to find it, to find it all? Wasn’t I meant to identify the smell as sex and move my body toward delivering itself? Wasn’t I meant to prove my worth, to carry on the weight of that room?

On my fourteenth birthday, I got a bottle of Jack Daniel’s from my brother. He was home from college for the summer. He gave it to me in secret, after dark, and we sat up in the attic window that connected our lives and drank it until I was bleary and swollen and unable to focus. At some point after midnight, we became overheated and half clothed. The heat works on you like that. You shed layers like the skin of a snake until the body can bear itself. My brother brought the whiskey to his face, took it, held it in his mouth like that with his eyes closed.

The Small Backs of Children

The Small Backs of Children The Chronology of Water

The Chronology of Water Dora: A Headcase

Dora: A Headcase The Book of Joan

The Book of Joan Verge

Verge